When the ao dai appeared, what the first ao dai looked like, are still imaginary...

Madame de Bassilan's painting of a Southern woman wearing a two-flap dress with the seam clearly visible in the middle of the front flap, printed with the article "Des habitants de la Cochinchine" written on January 8, 1859, without the author's name, reprinted in L'Indochine, Illustration.

Photo 1918, of Nguyen Dynasty women wearing five-panel shirts, open collars, blue or light green scarves, and black pants. (Photo: Albert Kahn)

Ao Dai: Origin

There is a legend that says "When the Trung sisters went to battle, they rode elephants, wore two-paneled golden armor, covered with a golden parasol, and were very splendidly decorated...". But in Viet Su Tieu An, Ngo Thi Si only wrote "When Ba Trac went to war, she had not yet finished mourning her husband, and wore beautiful clothes. The generals wondered, she replied: "Military affairs must obey the authority, if we keep the ceremony and make our appearance ugly, it will reduce our morale, so we dress beautifully to make the army mighty, the other army will see this and be moved, their fighting spirit will be weakened, then we will easily win". There is no sentence mentioning the yellow dress, the yellow parasol. Perhaps later generations thought that the king must wear a yellow dress, but in Lich Trieu Hien Chuong - Quan Chuc Chi (page 103) Phan Huy Chu wrote: "From the Ly and Tran dynasties onwards, the king's hat and dress could not be researched. As for the color of the dress, it seems that there was no definite regulation before. Le Dai Hanh (980-1005) used red cloth, until Ly Cao Tong (1176-1210) banned the people in the country from wearing yellow clothes, so the royal robe before was not the exclusive use of kings.

Some people say that the four-panel dress has existed since the Ly Dynasty, but they do not provide evidence. Phan Huy Chu could not even look up the royal hats and clothes of the Ly Dynasty, so how could he know about the clothing of the common people? In the past, history writing only focused on kings, famous people and important events, not many people paid attention to the clothing of the people.

Ao Dai: 17th century

- "Ao mo ba, mo bay" : When I was young, I heard about ao mo ba, mo bay but I only saw my mother wearing ao mo doi or ao mo ba, I never saw ao mo bay. These are long dresses worn one inside the other, the outer dress is usually dark in color like brown, black, can be plain or woven with shiny flowers on a matte background or vice versa, the inner dresses are all bright colors like lake water, pink, yellow... The custom wants people to be modest in the way they dress, the outer dress must use elegant colors, not showy, revealing, the bright colored dress must be hidden inside.

Later, I happened to read Relation de la nouvelle mission des Pères de la Compagnie de Jésus au Royaume de la Cochinchine (1631) by Priest C. Borri describing the clothing of Southern women as consisting of many different colored shirts intertwined, so I guessed that it was probably a type of shirt with three or seven layers. However, there are details that make me suspect that it is not ao dai, not sure if it is because the author is not clear or the French translator does not understand Italian well and has translated it wrongly: "Women's clothing is probably the most elegant and discreet compared to (the clothing of) all of India because it does not expose any part of the body, even in the hottest weather. They wear up to five or six layers of clothing, each one a different color. The outermost layer is long enough to touch the ground, dragging along in a solemn, noble manner, so that no one can see their toes. The second layer is below, shorter than the previous layer by about 4 or 5 fingers ("fingers" measured horizontally), the third layer is shorter than the second layer, and so on... so that all the colors of the clothes can be seen. This is the lower part from the belly down. The upper half is a short shirt that hugs the body, consisting of alternating white and colored squares like a chessboard, each layer a different color, covered on the outside with a smooth and thin material that makes it easy to see. easily seen through. All those mixed colors represent the fresh, graceful spring, while at the same time being very formal and modest. Men also wear five or six layers of long, wide silk shirts of various colors, with long, wide sleeves (...). From the waist down, the whole thing is cut sloppily, so that when going out in the street and encountering a light wind, all the colors flutter, blending together, looking no different from peacocks spreading their tails to show off their colorful feathers."

The outer layers of the dress were cut into long strips below the waist that Priest Borri mentioned, which was just the common lotus petal skirt . Or in some places called the rowing counter, which the ancients wore in front of the chest or below the waist outside the ao dai. The people of Hue called it the fringed leaf shirt. This skirt had three or four layers of silk strips sewn on top of each other. The innermost strip was the longest, then the outer layers got shorter. These strips are now simplified by sewing them loosely, smaller, and sticking three or four layers together. This costume is still occasionally seen during the village procession in the countryside of Northern and Central Vietnam, and in the royal dance costumes in Hue. The 17th-century statue of the Jade Lady carved in Dau Pagoda is the clearest evidence of the ao dai, the lotus petal strips, and the way the scarf is wrapped that Priest Borri witnessed four centuries ago. The ao dai and the way the scarf is wrapped in the statue from that time were no different from today.

Priest Borri also mentioned that the dark-colored robes worn by men and scholars at that time were similar to the outer garments worn by Catholic priests at that time. That is, similar to the five-panel ao dai of later times. He said that most Vietnamese men in the early 17th century, especially scholars, wore a black silk ao dai over other garments.

In 1819, when American captain John White visited Saigon, the dress code here was still the same as that seen by missionary Borri in Thuan Quang more than two centuries earlier. Mr. White mentioned a 16-year-old girl wearing black silk pants and a tight-fitting shirt that reached her ankles. He also said that men and women in Saigon at that time dressed similarly, with many layers of long dresses of different colors. The innermost shirt reached the ankles, then the outer shirts gradually got shorter... However, like now, the above dress code was only for the upper class. The clothing of the majority of people was more formal with dark colors.

Today we can still see traces of this style of shirt in men's ceremonial clothes, the outer shirt is made of thin blue or black gauze, clearly showing the white cloth lining inside, and the double-layered shirt (which existed before 1776, according to Le Quy Don), the outer surface is still black or brown..., the inner shirt turns into an undershirt (doublure) and still uses bright colors.

- Le Trieu Chieu Linh Thien Chinh recorded that in 1665 there was an edict: "Men's shirts have belts and pants have legs, women's shirts do not have belts, pants do not have two legs, from ancient times until now there has been an ancient custom like that. Singers in the theater do not follow this prohibition. Anyone who disobeys the order (...) and is caught red-handed will be fined five quan of ancient money, paid into the public treasury".

- Tavernier in Relation nouvelle et singulière du Royaume de Tunquin (1681) described the clothing of women in the North as "solemn and elegant. Men and women wear the same. The long dress reaches the heel, tied in the middle with a silk belt, mixed with gold and silver, the left and right sides are equally beautiful (...) They produce a lot of silk, rich and poor people wear silk". He also drew illustrations. Tavernier traveled to many places but had not set foot in the North, the details written in the book were based on the knowledge of his younger brother who had been to Dang Ngoai many times, and the times he talked with the Northerners he met in Batavia.

Ao Dai: 18th century

That is why S. Baron, born in Ke Cho (Thang Long), in Description du Royaume de Tonquin, translated into French in 1751, although acknowledging that Vietnamese people at that time, rich or poor, all wore silk because it was very cheap, criticized Tavernier for writing untruths. According to Baron, Vietnamese clothing was long dresses, similar to Chinese dresses, completely different from Japanese dresses. Tavernier's paintings show that Vietnamese people used belts, which was completely foreign to them. Baron was a mixed-race child with a Vietnamese mother, so he certainly understood Vietnamese customs better.

Some people write about the history of the ao dai roughly as follows: "Lord Vu Vuong Nguyen Phuc Khoat (1739-65) is considered the one who created and shaped the Vietnamese ao dai. Until the 18th century, Vietnamese people often imitated the way of dressing of the Northerners (China). To preserve their own cultural identity, Vu Vuong issued an edict on dressing, using the system of clothing and hats in Tam Tai Do Hoi as a model to create the ao dai, for all the people of Dang Trong to follow. Dai Nam Thuc Luc Tien Bien recorded this edict: "For regular clothes, men and women wear shirts with standing collars, short sleeves, wide or narrow sleeves as desired. Shirts with two armpits down must be sewn together, not allowed to be open. Only men who do not want to wear round-neck, narrow-sleeved shirts for convenience when working are allowed. And Le Quy Don, in Phu Bien Tap Luc, wrote that Lord Nguyen Phuc Khoat wrote the first pages of history for such ao dai. Therefore, it can be affirmed that the ao dai with its traditional, fixed form was born.

I found it inappropriate that Lord Nguyen wanted to maintain his "own cultural identity", forcing people to change their way of dressing to be different from the Chinese, but taking the clothing model from China's Tam Tai Do Hoi was unreasonable. I no longer had the two sets of Dai Nam Thuc Luc Tien Bien and Phu Bien Tap Luc in my hands, so I asked someone to help me find the section in Dai Nam Thuc Luc Tien Bien that talks about Lord Nguyen's edict, but I couldn't find it. I went to the bookstore to read another translation, but I couldn't find it either, so I just bought Phu Bien Tap Luc. However, I found completely different details in Phan Khoang's Lich Su: Xu Dang Trong:

- Page 616-617: Hoang Ngu Phuc, in 1776, after occupying Thuan Hoa, ordered: "The national costume has its own system, this locality has always followed the national customs. Now that the border is pacified, politics and customs must be unified. If there are still people wearing the clothes of the foreign people, they should change to follow the system of the country. Making clothes should follow the national customs and commonly use fabric and silk, only officials are allowed to use silk, satin, and brocade, and all kinds of dragon and phoenix patterns are not allowed to follow the old custom. For regular clothes, men and women should wear shirts with standing collars, short sleeves, with narrow or wide sleeves as desired. Shirts from the armpits down must be sewn closed, no slits allowed. Only men who want to wear shirts with round collars and narrow sleeves for convenience in work are allowed. For ceremonial clothes, use shirts with standing collars and long sleeves, light blue or black or white fabric as desired. As for the neckline or lining, all should follow the edict of the previous year."

- Page 615: Legend has it that Dao Duy Tu (1572-1634) plotted to oppose the Trinh family, advising Lord Hy Tong to force the people to change their customs to be different from the Northern people, such as abandoning the four-panel shirt, exposing the yem, and wearing a five-panel shirt with buttons, abandoning skirts and wearing pants, etc.

And the author also said that he copied from Vu Bien Tap Luc (Vu or Phu both mean "comforting" and pacifying the people).

I searched in Phu Bien Tap Luc and found another surprise:

- Page 241: "In the year of Giap Ty, the 5th year of Canh Hung (1744), Hieu Quoc Cong Nguyen Phuc Khoat proclaimed himself king. The crown and robe were made according to the book Tam Tai Do Hoi (...) "forcing the sons and daughters of Thuan Hoa and Quang Nam to change their way of dressing, wearing clothes like the Chinese, in order to show a complete change in the way of dressing of the ancients. Women and girls of the two regions had to wear short, tight-sleeved shirts like men's shirts (...). In just over 30 years, it became a habit, forgetting the old customs" (ie the customs of the North).

- Page 242: "In the year of Binh Than (1776) (3), the Nha Mon Tran Phu was established, and the Hiep Tran official (Le Quy Don) instructed the people: "The national costume has always had a system. This locality has previously followed the national customs (...) politics and customs must be unified. Those who still wear the clothes of the Khach people must change to follow the national customs (...). Clothes are made of ordinary silk. Officials are only allowed to wear xen sa, tru, doan (...). For casual wear, men and women only wear short-sleeved shirts with standing collars, with wide or narrow sleeves as desired. Shirts must be sewn together from the armpits down to cover the body, and must not be revealing. Men who want to wear shirts with round collars and narrow sleeves for convenience in work are also allowed. Formal wear must be shirts with standing collars and long sleeves or made of indigo, black or white fabric as desired. Those who are allowed to wear collared shirts and double-breasted shirts must follow the decree from the previous year. The reason why Le Quy Don, the Governor of Thuan Hoa in 1776, had to issue this decree was because the people of Thuan Hoa were rich and imitated each other in dressing lavishly and using beautiful colors.

- Page 13, in the Preface to Phu Bien Tap Luc: Le Quy Don added what he practiced when ruling Thuan Hoa, especially regarding clothing: "Change the old, strange way of dressing to follow the common customs of the dynasty (...) Forgive for a period of time before forcing everyone to completely change their old way of dressing".

I believe Le Quy Don more because not only was he a contemporary, an insider, but the details he gave were clear: because Lord Nguyen forced people to dress like China (1744), more than 30 years later (1776) when Le Quy Don came to guard Thuan Hoa, he changed the dress and forced people to return to national dress. Hoang Ngu Phuc was a military general who only fought and suppressed, and governing was the duty of civil servants.

Louis-Gabriel MULLET DES ESSARTS described in Voyages en Cochinchine 1787-1789: "The women's dresses were split in front from top to bottom, crossed at the chest and revealing silk trousers. I am not sure that they did not have shoes, but all the people I met were barefoot, men and women alike."

Ao Dai: 19th century

- In 1828, King Minh Mang issued an edict forcing women to abandon skirts and wear pants, which became the subject of four well-known satirical lines:

In August, the king issued a decree:

Ban crotchless pants, people are scared.

If you don't go, the market won't be crowded.

Go then exploit husband pants why?

- Michel Duc Chaigneau was of mixed race, his mother was Vietnamese, his father was one of two French officials serving the Nguyen Dynasty during the Gia Long and Minh Mang dynasties. Born in Phu Xuan, Chaigneau Duc wrote in Souvenirs de Hue quite meticulously about women's clothing: "The wives of merchants or small civil servants wore a short black or chocolate cloth shirt, black silk or white cloth pants. The people, the lower class workers, men like women, dressed very badly. Men only wore white or porridge-colored cloth pants, knee-length, tied around the waist with a long drawstring, hanging at both ends in front of the abdomen... Some wore short white or brown cloth shirts, usually torn, patched, not reaching the knee, revealing sunburned calves. Women dressed similarly, except the shirt was longer, the sleeves were wider, the pants and hats were wider. The upper-class, luxurious people wore double-layered silk shirts that were see-through, and silk pants reaching to the mid-calf."

Thai Dinh Lan (1801-1859), a Taiwanese, in 1835 took the provincial exam and returned by water, encountered a storm, drifted to Quang Ngai, and returned by land the following year. He traveled from the autumn of the previous year to the summer of the following year before arriving in Fujian, passing through 14 provinces of Annam such as Phu Xuan, Nghe An, Thanh Hoa, Thuong Tin, Lang Son, Thai Binh... and then through China before returning home. He wrote the book Hai Nam Tap Tru, recording what he saw and heard in the South. Regarding clothing, he said:

- Page 171: "Two officials came to our boat (to inspect). They all wore black silk scarves, narrow-sleeved shirts, red silk pants, and went barefoot (Vietnamese officials went barefoot wherever they went). They wore clothes that did not distinguish between hot and cold, even in the middle of winter they still wore thin silk clothes. The nobles mostly used two colors: blue and black; the same was true for their headscarves, and their pants were all red silk pants."

- Page 243: "Women go out to trade, with their hair in a bun, barefoot, using linen cloth to wrap around their heads, wearing hats made of buckets, wearing dark red silk shirts with narrow sleeves, long dresses reaching to the ground, not wearing skirts, not wearing lipstick, wearing pearl necklaces, agate beads or copper bracelets on their hands".

Cross-dressing shirt

It is not clear when it first appeared, I temporarily put it in the 19th century because it is considered the "oldest", having appeared before the four-panel dress, although no one has provided specific evidence. According to the Chinese, the ao dai originated from the cheongsam. However, the cheongsam only appeared in 1920 while the ao dai had existed for thousands of years before that.

The giao linh shirt is similar to the four-panel shirt, except that the two front flaps hang loosely, intersecting instead of being tied together in front of the belly. The giao linh shirt is sewn loosely, with slits on both sides, wide sleeves, and a long body that reaches the heels. The original design of the ao dai was a four-panel giao linh shirt made from four pieces of fabric, combined with a colored belt and a black skirt. This style of shirt has a cross-neck similar to the four-panel shirt. The giao linh shirt is worn over a brassiere, with a black skirt and a colored belt similar to the four-panel shirt, except that the two front flaps hang loosely, not being tied in front of the belly. Perhaps people found the giao linh shirt "loose", inconvenient for laborers, so they guessed that later a neater four-panel shirt was created.

The appearance of the ao dai originated from the ao giao linh, an early style of the Vietnamese ao dai, which appeared in 1744.

At this time, King Nguyen Phuc Khoat ascended the throne and ruled the southern region. The north was ruled by Lord Trinh in Hanoi, and the people there wore ao giao linh, a costume similar to the Han people. To distinguish between the North and the South, King Nguyen Phuc Khoat asked his assistants to wear long pants inside a silk shirt. This costume combined the costumes of the Han and Cham people. This may be the image of the first ao dai in history.

Images of Vietnamese women wearing Ao Giao Linh have been recorded in French documents. Ao Giao Linh is considered the original of ancient Vietnamese Ao Dai.

Four-panel dress

It is a type of shirt with four panels, the two panels of the back flap are connected vertically, the two front panels are tied together in front of the abdomen, leaving the bodice open. Belts in bright colors such as peach pink, lake water, yellow, banana green, young leaves... are slipped under the back flap, tied in front of the abdomen and then let down. This belt can be a "tower" or "purse" in the shape of a long tube, in addition to the function of decoration and keeping the shirt from being flaring, it is also used to hold money, by tying a knot and then putting the money in, then tying another knot to keep the money from falling out, tying it to the back, there is no fear of the money falling or being stolen. Some people say that the "four panels" symbolize the parents of both sides, the two front panels tied together symbolize the close relationship between husband and wife, clinging to each other... Honestly, I have just now learned these erudite explanations. At first it sounds reasonable, but I suspect that it was added by later generations for literary purposes, and I am not sure that the inventor of the shirt thought so, unless he was imitating China. If the two front panels tied together symbolize the intimate love between husband and wife, then when the two flaps of the shirt (giao linh) hang loosely and separate, it must symbolize that the couple has separated? Then the giao linh shirt must have appeared after the four-panel shirt, no one gets divorced before loving each other deeply!

According to researchers and artifacts at Ao Dai museums, the four-panel Ao Dai appeared in the 17th century. To make farming and trading more convenient, the ancients created a neat four-panel Ao Dai with two separate front flaps that could be tied together, and two back flaps sewn together into one flap. The ancients had to join the two back flaps to create the flap because at that time the fabric was only about 35-40cm wide. As the clothing of the common people, the four-panel Ao Dai was often sewn from dark fabric for convenience at work. This type of Ao Dai was often sewn in dark colors, symbolizing the four parents of the couple.

Shoulder changing shirt

Similar to the four-panel shirt, the difference is that the back flap is not simply a connection between the two panels, but each panel consists of two pieces: above the shoulder of each panel is a piece of fabric about a few spans long, but the two sides are alternately long and short, the left and right shoulder pieces are not even, and are usually a darker color than the body of the shirt, for example, if the shirt is light brown, the piece on the shoulder is dark brown or black. In my time, like the four-panel shirt, the shoulder-changing shirt was made of fabric, worn by people from the countryside, not people from the city.

Five-panel dress (Gia Long period)

Next, during the reign of King Gia Long, the five-panel ao dai appeared. This ao dai was sewn with an additional small flap to symbolize the wearer's social status. Urban women who did not have to work much often wore the five-panel ao dai to distinguish themselves from the poor working class. The five-panel ao dai had four flaps sewn together into two front and back flaps like the traditional ao dai, and on the front flap there was an additional flap as a discreet lining, which was the fifth flap. The two front and back flaps were both connected by two panels, under the front flap there was a small narrow flap, as long as the main flap. Halfway up the small flap, about knee-length, there was a strap attached to the main flap, at the seam. The flap was very wide, averaging 80cm at the hem. The front flap was cut longer than the back flap, and was sewn into a hammock so that the middle of the hem would not be loose and the chest of the ao dai would be pulled up when worn. The neck, sleeves and upper body of the ao dai of women at that time often hugged the body, the skirt of the ao dai was sewn wide from the side to the hem and did not have a waist. The sleeves were sewn together below the elbow. The reason the ao dai had to be joined like that was because good fabrics such as silk, gauze, brocade, and duan... in the past could only be woven up to 40cm wide. This style of ao dai had a loose shape, a collar and was popular until the early 20th century. The collar was only about 2cm high for women, and 3 to 4cm for men. But Hue women still kept their collars about 3cm high. Particularly in the North from the 1910s to 1920s, women liked to sew an additional buttonhole about 3cm on the right side of the collar and fasten the collar askew. The askew collar would be exposed to create a more seductive look, and also to show off the string of beads wrapped around the neck, inside the collar.

At that time, dark colored fabrics were used the most. In autumn and winter, brocade and silk were used. In spring and summer, silk and silk were used. Because the dyes were taken from natural materials of fabrics that easily faded, the ancients did not wash the ao dai made of expensive fabrics, and often used them as outer garments. These dresses were only dried in the sun a few times a year and then scented with agarwood or vetiver in a wooden box. Most of the ao dai in the past were sewn in double layers, meaning a lining layer was sewn inside. Especially when the dress was made of thin fabric to be discreet. This double layer was worn over the second ao dai inside. The inner lining absorbed sweat, so it was sewn in white fabric to avoid fading and to be easy to wash. The two layers of ao dai worn together with the blouse inside made up a set of three.

Pants worn with the ao dai were made to be moderately wide, over 30cm with a low crotch. At that time, most women from the South to the North wore black pants with the ao dai, while Hue women preferred white pants. Especially the upper class in Hue, both men and women, often wore the three-fold pants, meaning that along the two outer edges of the pants were sewn with three folds, so that when walking, the pants would flare out more.

The photo shows the distinction of classes in a family, the master wears a five-panel dress, the servant wears a four-panel dress (1884-1885)

Ao Dai: 20th century

According to cultural researcher Trinh Bach, until the early 20th century, most urban women wore ao dai in the form of five panels or five panels. The ao dai was loose-fitting, the pants were low-crotch, and only came in brown or black. In the South, there were other ways of wearing the ao dai, with more colors, but the colors were often not very bright. When weaving techniques were improved and the width of the fabric was increased from 40cm to at least double, many ao dai designers at that time, mostly artists, simplified the seam between the panels to have only three panels. The three-panel ao dai was born from that.

Lemur Ao Dai (1934 – 1943)

The bold breakthrough that contributed to the shape of today's ao dai was the "Lemur" ao dai created by artist Cat Tuong in 1939. The Lemur ao dai was named after his French name.

- In 1934, painter Nguyen Cat Tuong Lemur, a graduate of the Indochina College of Fine Arts (1928-1933 class) published a "manifesto" stating his basic views on ao dai reform, in the Phong Hoa newspaper:

"Moralists often say that clothes are just things used to protect against rain, sun, heat and cold, we should not pay attention to their luxury or beauty (...). In my opinion, although clothes are used to cover the body, they can be a mirror reflecting the intellectual level of a country. If you want to know whether a country is progressive or has fine arts, just look at the clothes of its people. The clothes of European and American people are not only very neat and suitable for their climate, but also have many and very beautiful designs. That is enough to show that they have a very high intellectual level, a very distinct and always progressive civilization. The clothes of girls, I see many inconvenient things but do not seem to be fine arts. Although in recent years there have been some changes (...) they are just in the bright colors, some strange foreign goods (...) but they still have the same flared shirts, the same black baggy pants. Or maybe there are people who like to wear white pants, but unfortunately that number is still very small (...). This needs to be gradually changed.

First, he analyzed and presented the advantages and disadvantages of contemporary women's clothing, then he proposed innovations that were suitable for the weather, comfortable to move in, spacious for blood circulation and enhanced the elegant and graceful beauty of women. The clothing designs he designed were named after his French pen name: "Lemur Shirt".

In the Spring issue of February 11, 1934 in Phong Hoa newspaper, editor Nhat Linh opened a new column called “Private beauty for ladies” by Mr. Cat Tuong. He had many articles instructing women on how to beautify themselves such as how to apply powder, lipstick, how to paint nails, how to exercise to keep a beautiful figure..., but importantly, he called for a reform of women's clothing and had the boldest reform of the Vietnamese ao dai. He introduced Western elements into the ao dai. In the weekly "Phong Hoa" issue 86, published on February 23, 1934, with the title "Women's clothing", artist Cat Tuong gave his opinion on the reform of the ao dai:

“What should the clothes of the girls be like? First of all, it must be suitable for the climate of our country, the weather of the seasons, the work, the frame, the size of each of your body, then, it must be neat, simple, strong and have an aesthetic and polite appearance. But no matter what, it must have the unique character of our country. You are Vietnamese women, so your clothes must have a unique appearance so that others do not mistake you for foreign women. Try to notice if there is anything inconvenient or redundant in your current clothes? God created people, inherently with their own shapes, the parts that are open and the parts that are tight to suit all aspects of aesthetics, not smooth like a candy box or a Nestle tube. Therefore, the clothes must fit the person, must have a civilized style so that that beauty can be revealed. Next, the design must be added or subtracted depending on each person. For example, a thin person's shirt must have many pleats (folds) (The more you add, the more the fat person's shirt should be neat so that it doesn't look skinny or sloppy. If you want me to understand those modifications or additions, from the next issue, I will gradually show you the models I have thought of...".

Officially appearing in the Phong Hoa issue on March 23, 1934, the Lemur ao dai was designed based on the three-panel ao dai that had been created before. Different from the traditional loose shape, the Lemur ao dai hugged the body's curves with many Europeanized details such as puffed sleeves, heart-shaped neckline, and bow studs. The Lemur ao dai had a round or lotus-leaf neckline, ruffled, or wide-cut to expose the neck, and lace trim. The shoulders were puffed or sleeveless, and the back was exposed to the waist. The drawstring trousers were replaced with bell-bottom pants with buttons on the side or with ties; the pants were tight from the hips to the knees and then flared out to the hem like a loudspeaker.

In terms of color, he advocated abandoning the traditional dark brown. Lemur Ao Dai often has soft, elegant and bright colors according to the sophisticated aesthetics of Europeans. In each style of Ao Dai, he carefully noted the type of fabric, weather, suitable skin color or body shape. Through each issue, he instructed women on how to dress fashionably, convenient for daily activities. To encourage, he launched the "Healthy and Beautiful" women's movement, encouraged women in the country to exercise and instructed them on how to apply makeup. He also organized fashion shows across Vietnam, from North to South.

Old Hanoi girls with Lemur ao dai |

Queen Nam Phuong wearing Lemur Ao Dai |

Specific features of Lemur Ao Dai:

- Collar: Western-style collar, sharp corners are called "knife collar", round is called "bread collar", heart-shaped collar, tied with string..., all open in the middle of the chest, only the turtleneck with puffed shoulders opens on the right shoulder, buttons from neck to shoulder.

- Western plastic buttons, square, round, oval... and with raised or sunken flowers, in a variety of colors to choose from depending on the color of the shirt. The type of buttons made of woven fabric like the Chinese are no longer used, but I used to wear shirts with this type of button, it was very difficult to fasten or unfasten because the fabric was tight and not smooth like plastic buttons. Plastic buttons were later replaced around the 1950s with imitation pearl buttons designed by Ms. Le Thi Luu.

- Sleeves: Mr. Cat Tuong commented that the traditional sleeves are narrow and very inconvenient when bending the arms, and are not suitable for hot climates... However, he has drawn a style of evening gown with sleeves cut short at mid-arm and wearing gloves (gants) that reach mid-arm. Some people praised it as looking "very luxurious", but some people who wear it feel that replacing the long sleeves with a pair of long gants is even hotter and more inconvenient.

- Body of the shirt: Mr. Cat Tuong said that the traditional shirt was too loose, it needed to hug the body of the wearer to be beautiful. However, clothes were not only for the purpose of protecting against rain, sun, heat and cold and to be artistic as he said. In the past, it was also to cover the body, women were not allowed to expose their bodies to outsiders. My eldest sister also had to corset her chest, wrap cloth around her chest several times, and press it down to make her chest flat. Mrs. Bui Thi Xuan, when she was imprisoned by Gia Long before being executed, asked someone to buy white silk to wrap all her limbs so that when she was executed (elephant throwing), her body, even if it was only a piece in each place, would not be exposed (Lemonnier de la Bissachère). In fact, the Lemur shirt only hugged the wearer's body loosely, not tightly. Just look at Mr. Lemur's own wedding photo (1936) and you can clearly see that both the bride and the bridesmaids wore the Lemur shirt, but it did not really hug the body like today's ao dai, but was only less baggy thanks to the curves cut to follow the body shape, not deep pleats, sometimes without plis at all. In 1952, my friends and I were still wearing ao dai without plis. Maybe because Mr. Cat Tuong only drew the yếm style but did not think about drawing the soutien (some people translated it as "nít tho" which is not correct because "nít" means to compress down while soutien lifts the chest up). There is a distance no less from the Lemur shirt to the modern ao dai than there is from the loose ao dai to the Lemur shirt.

- Hem: The traditional ao dai requires 3 stitches and a long band to hem the hem to make it stiff, the flap will stand up and not curve. Mr. Cat Tuong introduced a circular hem made of a different material and color than the shirt, similar to the hem of pajamas, less labor-intensive and eye-catching. The hem color is the same as the button color.

In 1937, to make the clothing innovation successful, and to satisfy women who wanted to wear modern ao dai, to feel more beautiful, more graceful, and more charming, painter Cat Tuong opened the LEMUR Tailor Shop.

Lemur's reform of the Ao Dai has truly opened a new chapter for the modern Ao Dai, making it much more charming and luxurious. Lemur Nguyen Cat Tuong's greatest success is that he has contributed to changing the general aesthetic concept of women's clothing. Later, many artists continued to improve the Ao Dai, blending it with the traditional national dress to honor the graceful beauty of women.

Lemur's reform of the Ao Dai has truly opened a new chapter for the modern Ao Dai, making it much more charming and luxurious. Lemur Nguyen Cat Tuong's greatest success is that he has contributed to changing the general aesthetic concept of women's clothing. Later, many artists continued to improve the Ao Dai, blending it with the traditional national dress to honor the graceful beauty of women.

However, this “hybrid” shirt was strongly condemned by public opinion at that time, considered indecent, so only modern artists dared to wear it. By 1943, this style of shirt was gradually forgotten.

Le Pho Ao Dai

Although the Lemur Ao Dai was welcomed, it was also criticized as "hybrid". According to Wikipedia, Mr. Le Pho, also in 1934, "modified the hybrid features, added ethnic elements from the four-panel and five-panel Ao Dai, creating an ancient long-flap style that hugged the body, while the two lower flaps were free to fly, harmoniously merging. The Ao Dai had found its standard shape". The Le Pho Ao Dai is a new combination of the four-panel and the Lemur Ao Dai. He reduced the size of the Ao Dai to hug the body of Vietnamese women, pushed up the shoulders, lengthened the flap to touch the ground and brought many new colors, making it more sexy, sophisticated and attractive. From then until the 1950s, the Vietnamese Ao Dai style became extremely famous in the country's tradition. According to Hoang Huy Giang, Le Pho "eliminated Western features such as sleeveless, puffy sleeves, open collar, no round hem, long flaps, etc.

Le Pho Ao Dai is often combined with white flared pants, a style that Vietnamese women have favored for a long time. This Ao Dai model is considered the "totem" of later Ao Dai, contributing to the development and tradition of Vietnamese traditional costumes.

"Family Life" by artist Le Pho (1907-2001). The silk painting measures 82 x 66cm and was made between 1937-1939 (Photo: Sotheby).

“Lemur Ao Dai” and “Le Pho Ao Dai”

In the book “Lemur Ao Dai and the Context of Phong Hoa & Today” (Khai Tam Books, Hong Duc Publishing House, December 2018), author Pham Thao Nguyen clarified a misunderstanding related to “Le Pho Ao Dai” and “Lemur Ao Dai”. Documents collected and preserved by Mr. Nguyen Trong Hien – the son of artist Lemur, show that during the women’s clothing reform movement at that time, artist Le Pho actually only created jewelry and published it in the first “Dep” special issue – Muon Nuc 1934 by artist Cat Tuong.

However, in the interview “Mrs. Trinh Thuc Oanh talks about Fashion” by journalist Doan Tam Dan, published in the first issue of “Ngay Nay” (January 30, 1935), Ms. Oanh said: “…The white and fragrant ao dai was the “fashion” of 1920. That year is long gone. During those years, women only knew how to search for fabric samples to sew clothes to replace the dark black ao dai of the past, but it was still not suitable for the body, and did not highlight the special beauty of each person. The style of shirt suitable for the body, the elegant and versatile style, was created for women by the two artists Cat Tuong and Le Pho. Many people followed it, and this style of shirt became a new fashion…”

In the weekly newspaper “Ngay Nay”, issue 77 on September 19, 1937, Marie advertised “the style of painter Le Pho”, however it is unclear whether it was the style designed by Mr. Le Pho or he was just advising on choosing the “Lemur ao dai” styles available in the special issue “Dep”. However, Mr. Hien said that he had visited the wife of painter Le Pho when he had the opportunity to go to Paris, and she confirmed that painter Le Pho had never invented or designed the ao dai.

Raglan Ao Dai

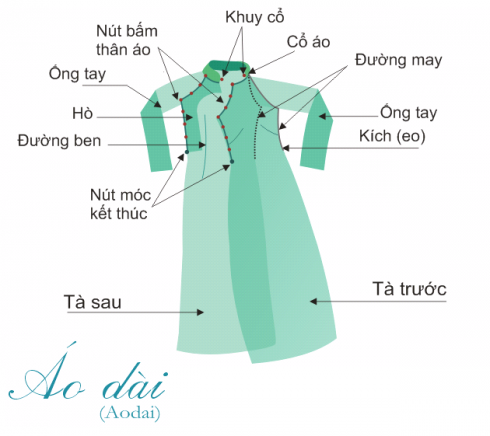

The way the ao dai was sewn at that time had a major drawback: wrinkles were very likely to appear on the armpits. In the 1960s, Dung tailor shop in Dakao, Saigon introduced the method of attaching raglan sleeves to the ao dai. The biggest difference of the Raglan ao dai is that the ao dai hugs the body more closely, the way the sleeves are joined from the neck diagonally down at a 45-degree angle helps the wearer to be more comfortable and flexible. With this method, the sleeves are joined from the neck diagonally down to the armpits. The front flap is joined to the back flap via a row of buttons from the neck down to the armpits and along one side of the hip. This method of joining minimizes wrinkles at the armpits, allows the flap to hug the wearer's curves, and helps women move their arms comfortably and flexibly. From here, the Vietnamese ao dai was shaped. Then there were the mini and maxi raglan styles.

Lady Nhu's Ao Dai (early 1960s): Bold and meaningful reform

In the early 1960s, Mrs. Tran Le Xuan, wife of Mr. Ngo Dinh Nhu, designed a long dress with an open neckline, without the collar, also known as the boat neck (bateau), a scoop neck and short sleeves. This dress became famous as the Mrs. Nhu ao dai and was met with strong reactions because it went against the traditions and customs of the society at that time.

However, the Ao Dai Ba Nhu is also a significant reform. Previously, the traditional Ao Dai often had a high standing collar, causing discomfort and inconvenience to the wearer, especially in the hot weather of Vietnam. The Ao Dai Ba Nhu with its comfortable boat neck solved this problem, at the same time helping the wearer become more dynamic and modern.

Later, the modernized ao dai appeared more diversely with comfortable collar designs such as sweetheart neck, round neck, boat neck, square neck, etc., but still retained its traditional beauty. Catching up with the new fashion trends, famous ao dai tailors at that time such as Thanh Khanh and Dung Dakao simultaneously introduced embroidery designs on silk or eye-catching floral paintings on the ao dai flap, while updating many new fabric motifs and colors.

Not only that, Saigon women also gradually abandoned their traditional chemises and replaced them with Western lingerie. The cup-shaped bras that were popular in the world in the 1940s gradually became popular in South Vietnam in the 1960s.

It can be said that the Ao Dai Ba Nhu is a start for bold and meaningful reforms to the traditional Ao Dai. It has contributed to making the Ao Dai more modern and suitable for modern life, while affirming the fashion and cultural value of traditional Vietnamese costumes.

Mrs. Tran Le Xuan, the initiator of the movement to wear boat-neck ao dai

(Photo: Harrison Forman)

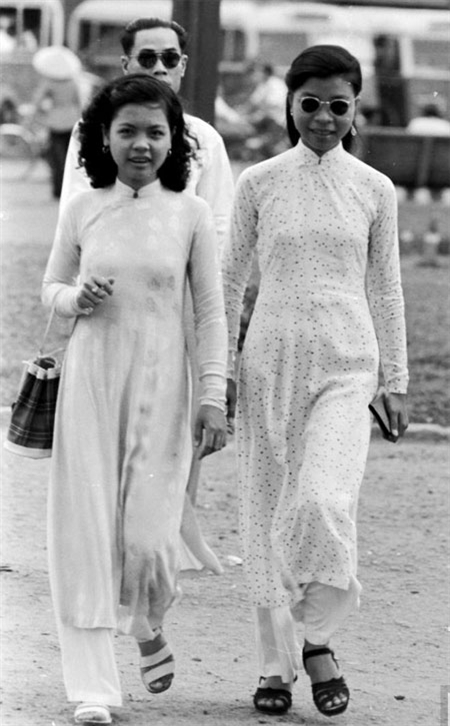

Being sensitive to updating new fashion trends while still maintaining the traditional beauty contributed to "raising the level" of fashion sense of Saigon ladies at that time. They appeared in a very innovative and "rebellious" way in elegant ao dai, bouffant bob hair, silk scarves and did not forget to wear luxurious cat-eye glasses. That image was like the perfect intersection between Eastern and Western fashion in the 50s.

Ao dai with tight waist – mini ao dai (1960 – 1970)

In the 1960s, the Ao Dai with a tight waist challenged traditional views and became a fashionable style. At this time, the convenient corset was widely used. Urban women with open minds wanted to highlight their body curves through a very tight Ao Dai with a tight waist to enhance their bust.

Towards the end of the 60s, the mini ao dai became popular among schoolgirls because of its comfort and convenience. The skirt was narrow and short, reaching almost to the knee, the shirt was loose and not tight at the waist but still tailored to the body's curves.

Three-panel shirt

In the 70s, some tailors in Saigon launched a three-panel shirt style with one back flap and two front flaps with buttons from the neck to the waist worn with elephant-leg pants.

Modern Ao Dai (1970 – present)

After the 1970s, the changing lifestyle made the ao dai gradually disappear from the streets. However, from 2000 to now, the ao dai has returned with many different designs and materials through creative and innovative collections by designers Vo Viet Chung, Si Hoang, Thuan Viet... Not only stopping at the traditional design, the ao dai has been transformed into wedding dresses, short-sleeved dresses to wear with jeans, collarless shirts... Most people wear plain or embroidered shirts instead of painted shirts, and the embroidery covers almost the chest, leaving no room for jewelry. There are also pullover ao dai without buttons. Pants are the same color as the shirt or completely different colors such as red, yellow, blue...

The Ao Dai has changed throughout the ages, from the Giao Linh Ao Dai to the modern Ao Dai, from an everyday dress to a national symbol. When Vietnamese women put on the Ao Dai, they feel a surge of pride and confidence. The Ao Dai has also become the foundation for variations such as wedding dresses, modernized Ao Dai, and still retains its graceful, sexy, and discreet features that no other outfit can replace. Under the influence of the dynamic trend and changing modern lifestyle, the traditional Ao Dai has been stylized by designers with shorter skirts, changed collars and sleeves, and even creations with skirts or pants worn with the Ao Dai, giving Vietnamese women many choices. This stylization has made the Ao Dai more popular in the daily lives of Vietnamese women. We can see colorful, unique Ao Dai with many new designs appearing not only in offices, sacred temples, but also when walking on the street.

Today, many women choose the ao dai as their daily outfit. The ao dai is suitable for our country's climate, the weather of the seasons, our work, the shape and size of our body, highlighting the gracefulness, sexiness, and modesty that no other outfit can replace. Furthermore, the ao dai is neat, simple, strong, and has an artistic and polite look, shaping the style of young, dynamic Vietnamese women, blending in with the promotion of the country's unique character.

With such a long history of development, the Vietnamese Ao Dai has become more perfect than ever and has become an indispensable symbol in Vietnamese culture, enhancing the beauty and elegance of Vietnamese women. The Ao Dai is not only a costume representing a culture, but also an endless source of inspiration for Vietnamese art. This is a symbol of constant creativity in the cultural heritage of the nation.

Ao dai designs use breathable natural materials suitable for tropical climates such as Vietnamese silk and linen from sustainable fashion brand Hity.

Source of information:

1. Ao Dai past and present - Nguyen Thi Chan Quynh http://chimviet.free.fr/quehuong/chquynh/chquynh_aodaixuanay.htm

The article is quoted verbatim from the author. "I" in the above article is Nguyen Thi Chan Quynh

2. Harper's Bazaar Magazine

0 comments